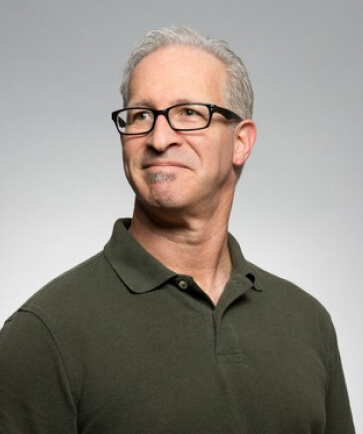

A groundbreaking study suggests that risk factors and blood biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease may be detectable in individuals as young as 24 years old. Allison Aiello, James S. Jackson Healthy Longevity Professor of Epidemiology at Columbia University, is at the helm of this pioneering study. It uncovers the electrifying potential of detecting early indicators of cognitive decline long before the typical diagnostic threshold of 65 years.

Today, an estimated 32 million people worldwide are living with Alzheimer’s disease. This debilitating neurodegenerative disease is frequently diagnosed only after symptoms manifest in early adulthood and beyond. Previous studies have shown that Alzheimer’s-related biomarkers may be detectable up to 16 years prior to an official diagnosis. The recent results further our understanding of how cognitive decline occurs. Most unexpectedly, they propose that telltale signs can even be detected in people as young as their twenties.

“These findings provide early evidence supporting the view that Alzheimer’s disease is a lifelong process, with underlying changes potentially beginning much earlier in life than previously recognized,” said Aiello. Specifically, the researchers aimed to determine if cognitive measures such as immediate recall, delayed word recall and working memory are associated with cardiovascular and inflammatory risk factors. Unlike other studies, they concentrated on younger people.

The analysis revealed that traditional cognitive measures are associated with these risk factors. This third link is evident even among adults who are only in their late twenties. “The fact that standard cognitive measures show measurable associations with cardiovascular and inflammatory risk factors in adults as young as their late 20s is striking,” noted neuropsychologist Jasdeep S. Hundal, who specializes in cognitive change across the lifespan.

Aiello emphasized the importance of understanding these biomarkers: “Because Alzheimer’s is a progressive and multifactorial disease, its biological underpinnings are often in motion long before symptoms are evident.” The researchers are convinced that with early intervention, advancement of the disease can be greatly delayed. By starting work earlier, they aim to stop its advancement before it even begins.

The study brought attention to the CAIDE risk score. It’s long been a good predictor of who will get Alzheimer’s disease, sometimes decades before an official diagnosis. “Further, cardiovascular health is an important predictor of Alzheimer’s disease,” Aiello stated. “Given that our study population was relatively young and did not yet have significant cardiovascular disease, we were interested to see if the CAIDE risk score predicted cognition in young generally healthy individuals.”

One very interesting aspect of the study findings, that they acknowledge come as a surprise, is the timing and nature of genetic risk markers associated with cognition. Aiello noted, “The reason the relationship between this genetic risk marker and cognition emerges later in life but not earlier remains unclear.” According to researchers, it has been hypothesized the impacts the APOE e4 gene can have may be cumulative. They think these effects might be amplified after middle age, perhaps due to environmental or biological influences.

Hundal asserted the urgency for further research: “If we wait until cognitive deficits are clinically observable, we’ve already lost valuable time for intervention. That’s why continued research into early, preclinical markers of risk is not just important. It’s imperative!”

Leave a Reply